Dear Everyone,

St. Francis, Paperbacks and Road Trips

“Lord make me

an instrument of your peace

Where there is hatred,

Let me sow love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, Joy.

O Divine Master grant that I may

Not so much seek to be consoled

As to console;

To be understood,

As to understand;

To be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned.

And it is in dying that we are

Born to eternal life.”

You can listen to a musical version of St. Francis’ prayer performed by Sarah McLachlan, here.

Kindness is never wasted

Dear Everyone,

Music – “Bésame mucho”

Dear Everyone,

Dante, Sex and God

Dear Everyone,

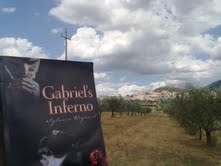

There is a scene in “Gabriel’s Inferno” in which the main character gives a lecture at the University of Toronto on the topic of Lust in Dante’s Inferno. Professor Emerson is very familiar with lust and its various forms and some of his expertise emerges during his presentation.

In an interview that I did recently with Tigris Eden, (which you can read here), I identified Gabriel as a sensualist. He’s obsessed with the pleasures of the body – taste, touch, sound, smell, sight. You can see this in his choice of Scotch, food, sex, art, music, fine clothing and writing instruments, etc.

Julia is very different from Gabriel. She is a product of her upbringing and circumstances, but also of her choices. Rather than focusing on the pleasures of the body, she has favoured the pleasures of the soul – education, friendship, and love.

Throughout the course of the novel, the topic of sex is raised by different characters who espouse different views of it. Last week’s post was a glimpse into the music and ideas associated with Julia and her past. Several readers commented on the music and lyrics of the song. I enjoyed reading their reactions and so this week I welcomed readers to contact me via Twitter, Facebook or email to share their ideas about the connection between sex and God.

The response was overwhelming.

Many readers emphasized the connection between partners that emerges through sex – a connection of knowledge, intimacy, and giving. Some readers emphasized the transcendence or the sublime as it’s experienced in sex.

Readers identified themselves as coming from various different perspectives – some religious, some not. In all, I was surprised at the similarity among the comments and how reader’s reflections overlapped with my own views.

Over the course of writing a story that presents the redemption of sex as much as the redemption of a man, I’ve wondered about the relationship between sex, love and God. I’ll never be able to do justice to these connections in this short post, but I’ll present some of my reflections so far.

My suspicion is that sex offers human beings a glimpse of the transcendent in the way nature or human creations caused the Romantic poets to think of the sublime, or what Wordsworth termed “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.”

If a Grecian urn, frost, or the ruins of an old abbey can inspire such reactions, how much more can sex? And if the powerful feelings elicited by nature or artifacts provoke us to think about our place in the world, how much more can sex provoke us to think of similar things and beyond?

What I have in mind here is the way that sex is all-consuming during the act and especially, during orgasm. Sex focuses all attention on the attainment of its goal – satisfaction. But one can also think of sex as a symbol of something else. The greatest of bodily pleasures could be seen as a foretaste of Dante’s Paradise,where one is known and loved intimately by the Divine and all one’s desires are satisfied, not just for moments but for eternity.

When Dante visits Paradise, he meets St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153). In description of the meeting Dante writes, “Though he had been absorbed in his delight, that contemplator freely undertook the task of teaching.” [Canto 32.1]

“The King through whom this kingdom finds content

in so much love and so much joyousness

that no desire would dare to ask for more.” [Canto 32.61]

I’m sure everyone has their own idea of what heaven is like, if they believe in heaven. I have a fondness for Dante’s vision – that heaven is a place of absorbing delight, where everyone is content, loved and joyous, and one’s deepest and best desires are satisfied to the point where there is no more desire.

It sounds similar to sex, doesn’t it?

In the closing lines of the end of his Paradiso, Dante pens the following:

“But then my mind was struck by light that flashed

and, with this light, received what it had asked.

Here force failed my high fantasy; but my

desire and will were moved already—like

a wheel revolving uniformly—by

the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.” [Canto 33]

Through his visit to Paradise, Dante is given insight into the workings of the universe. Everything is governed by love. From a Dantean perspective, then, it doesn’t seem to be too great a leap to suggest that sex within the context of love is a picture or an image of Paradise.

Once again, I welcome your thoughts below. Thanks for reading,

SR

PS. If you have friends who are interested in reading “Gabriel’s Inferno,” please let them know about two contests in which they can enter to win a copy.

Also, you can read reviews of my book in languages other than English here.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- Next Page »

I am honoured to have had all three of my novels appear on the New York Times and USA Today Bestseller lists. I was a Semifinalist for Best Author in the 2011 and 2012 Goodreads Choice Awards. {

I am honoured to have had all three of my novels appear on the New York Times and USA Today Bestseller lists. I was a Semifinalist for Best Author in the 2011 and 2012 Goodreads Choice Awards. {